Can you feel the power? The 4 week training block

You probably aren’t getting the most out of your training. Lack of rest and recovery is why.

How often do you rest? How often do you deload?

If you are like a lot of people I see on my Facebook feed, the answer is rarely or never. A lot of people take pride in the fact that they don’t rest often or that they don’t taper before comps. I just shake my head when I see that. That isn’t bad ass to me. That isn’t cool to me. That is just plain stupid.

You get better at rest. You need rest for supercompensation to occur, which is to say you need to rest for your body to optimally adapt to the stimuli to which you are exposing it. If you don’t care about performing your best in a competition or about consistently making the best gains you can, then by all means this article isn’t for you. If you want to train smarter, get the most out of your training, and be less likely to experience overuse injuries, then please read on.

A lot of people don’t like to rest or taper because they feel they are losing gains. This is totally natural especially so for the people who do like to compete since that speaks to an enjoyment of physical activity. We’ve been active for so long that we just don’t feel right when we rest. Likewise tapering and peaking for a specific competition is as much art as science since it’s so different person to person, so you may have experimented with this before and gotten bad results. It will take a few times of tweaks before you get it right. Since whole books can be written on the taper and peak, I’m going to put to that aside and just discuss how to build in rest and recovery to your schedule.

First, you may need a primer on what exactly supercompensation is. It is the period of time where your body adjusts to the training load you have put it through, and your fitness level rises. To steal from the wiki page about it, training can be broken down into 4 periods: initial fitness, training, recovery, and supercompensation. While there is no gold-standard for amount of time needed for supercompensation to occur there are two constants: If you don’t rest, supercompensation will occur minimally or not at all/If you do rest, you give your body time for supersompensation to occur. At its core, this is what a training cycle will look like.

You enter in at a specific level of fitness, train to the point of potentially seeing a fitness degradation, rest, compensate

Your training year will be broken into these constant undulating waves where the trough and peak of the current cycle is a little higher than that of the previous cycle. It is about steady, systematic, small but regular improvements while maintaining your body’s health. It’s not random. It’s not go hard all the time. It’s smart and measured.

How does one structure their training to take advantage of this phenomena? Simple. Use the 4-week training block.

What is the 4-week training block?

The 4-week training block is 3 weeks of increased training load followed by a deloading week of a greatly reduced load. It is used by a lot of a great coaches in both the endurance, strength, and conditioning worlds. Take a look at powerlifting trainer Jim Wendler’s famous 5-3-1 system that a lot of CrossFit gyms implement for their strength program. Joe Friel who literally wrote the Bible on triathlon training uses it. Ross Emanit of RossTraining uses it. The list can really go on and on.

How does it work?

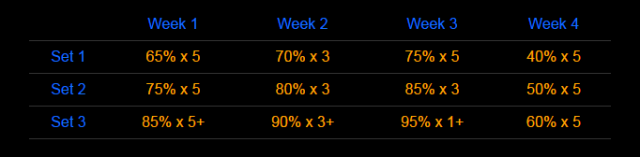

It’s pretty simple from both a weightlifting and an endurance training perspective. A weight lifting example lifted from Wendler’s work would be something like this:

Week 1 – Cycle 1: 85%1RM for 5+ reps

Week 2 – Cycle 1: 90% 1RM for 3+ reps

Week 3 – Cycle 1: 95%1RM for 1+ rep(s)

Week 4 – Cycle 1: 60%1RM for 5 reps

Week 1 – Cycle 2: Add 5-10lbs to previously calculated 1RM and repeat week 1… etc

You aren’t hitting the gym looking to lift as much as possible every day. You aren’t sticking to the same loads and rep schemes every week. You are systematically increasing the intensity (%1RM) for 3 weeks, backing off for the sake of recovery and compensation, and then starting and ending a new 4 week cycle just a touch higher than the previous one. For some people, this approach seems too slow. While it doesn’t promise quick gains like every infomercial-like fitness promise out there, it gives you consistent gains for years and years and years without the expense of over-training or injury.

From an endurance perspective, we would focus on volume meaning the total amount of training hours. As I explain in “Hey you! You’re training too hard. Stop it!”, your endurance training should follow specific intensities based on the hours you train. To simplify this, it would be around a 90/10 split between low intensity/high intensity. For example if your run for 10 hours this week, 9 hours would be in zone 1/zone 2 (under threshold) with 1 hour of total time at zone 4 or higher (above threshold). That 1 hour is for total work time in an interval session. It doesn’t count rest. It may seem like little, but 1 hour of zone 4 intervals is crazy hard and would be best served to be spread between 2 sessions.

From my own example for my 1st and 2nd base period:

(No tapering built in prior to shown races because they were low priority races that I was “training through”)

Week 1 – Cycle 1: 14.5 hours

Week 2 – Cycle 1: 16.5 hours

Week 3 – Cycle 1: 18.5 hours

Week 4 – Cycle 1: 10 hours

Week 1 – Cycle 2: Tack on an hour to the ending work weeks of the cycle

Endurance training is a little different in that increasingly it is shown that training time is more important than training intensity. For example, somebody training 10 hours at a slow pace will generally undergo better gains than somebody training 5 hours at a fast pace. Again, that is explained in my previous article.

But wait! There’s more!

Testing! Being able to make regular systematic gains is only half of it in terms of endurance training. Your deloading weeks can contain testing to make sure your training is on the right track. Say if all you’re concerned with is your running, then you can complete a 3 mile time trial near the end of your dealoading weeks. An indoor track would be best for this since that would limit variability from external factors like heat, cold, and weather (rain, snow, etc), but regardless you should see a gradual downward march of your finishing time. If you don’t for a few blocks, then something needs to be adjusted in your training. The added benefit of this is also that a 3 mile time trial is a common way to benchmark your max heart rate. Every 4 weeks, you’ll be able to tweak your HR training zones to be as accurate as possible.

The long and short of it.

This was more long than short, but I hope you see that the 4-week training block is a simple but powerful tool to use when programming your training and looking ahead toward your race season and even years in advance. Think of evolution. Small, gradual but consistent changes over a long period of time can add up to quite a large change.

Pingback: Hey you! You’re training too hard. Stop it! | Will Work For Adventure